Codex Annamiticus: A Book of Remedies from 14th Century Ireland

Codex Annamiticus is my first long-form medieval art project. It is an original manuscript which may plausibly have been owned and used by a physician living in Ireland in the late 14th or early 15th century. Codex is the technical term for a medieval book; handwritten, usually on parchment, and bound along one edge. The term appears in the modern names of many medieval works, e.g. the Riesencodex, Florentine Codex, Codex Argenteus, etc. Annamiticus (-a, -um) is an adjective meaning 'Vietnamese', according to the Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum, a trilingual Vietnamese-Portuguese-Latin dictionary, published in 1651. Most of the calligraphy was done in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, making this project the "Vietnamese Book".

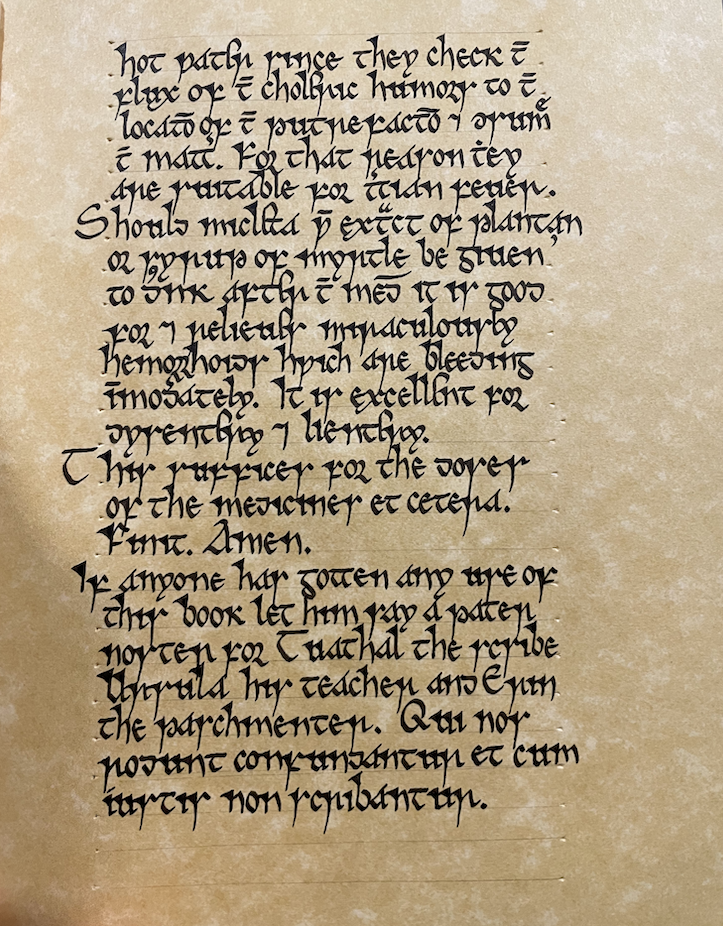

High Resolution Images of Selected Pages

- Goals

- Historical Context

- Text

- Script

- Page

- Size

- Decoration

- Materials & Methods

- Doing the work

- Progress on the work

- Finishing the book

- About the Scribe

Goals

Create an artifact that can be worn and displayed as part of my SCA persona.Why I scrapped this goal- Learn more about the history of bookmaking in Ireland.

- Improve my calligraphy.

Historical Context

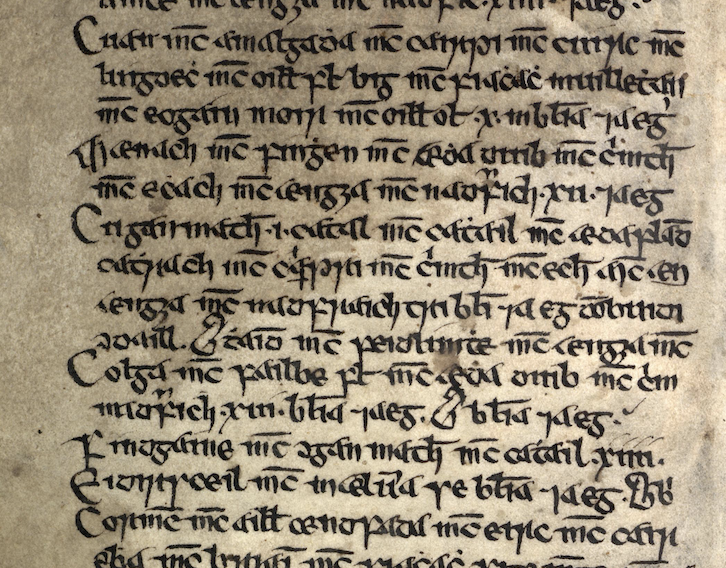

I started by researching the time and place in which I wanted to make my book. My major sourcers were academic papers about individual manuscripts which discuss the purposes and economy of bookmaking, and also the lives of individual scribes. This helped put me in the proper mindset to make informed creative decisions. The Book of Ballymote (Royal Irish Academy MS 23 P 12), an Irish manuscript created in the late 14th or early 15th century, was the main focus of my research. Pádraig Ó Macháin has published a very informative paper on its particular context.

In the 14th century, large parts of Europe had a flourishing secular book trade that supported a class of professional scribes. This was not so in Ireland, where educated professionals such as doctors and lawyers produced books for themselves, accumulating libraries for the family trade over generations. Apprentice lawyers were required to copy the law as part of their training. These were not the illuminated manuscripts, but practical texts, with little or no decoration.

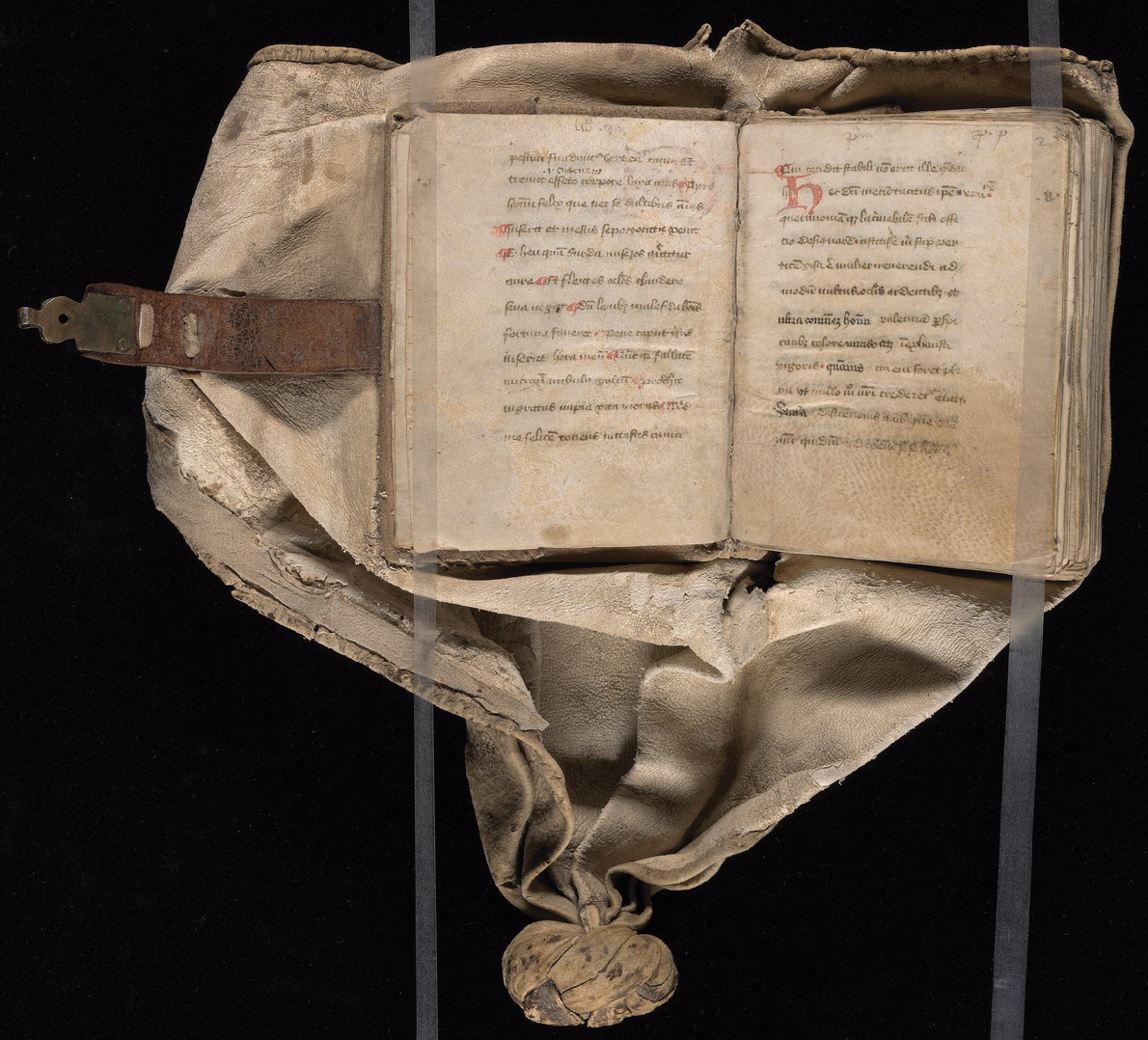

I was also inspired by other objects I had seen in the SCA, namely a girdle book that was gifted to one of my friends at her elevation to the Order of the Laurel. A girdle book is a small book bound in such a way as to allow it to be hung from the belt; these were popular among traveling clergy and lawyers who needed to have a book conveniently at hand, and among lay women who wanted to carry a personal prayer book such as a Book of Hours. Originally, I wanted to make a girdle book, but in the end decided that binding was outside the scope of the project. Still, Codex Annamiticus is of a size that is could be easily bound as a girdle book.

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

The Text

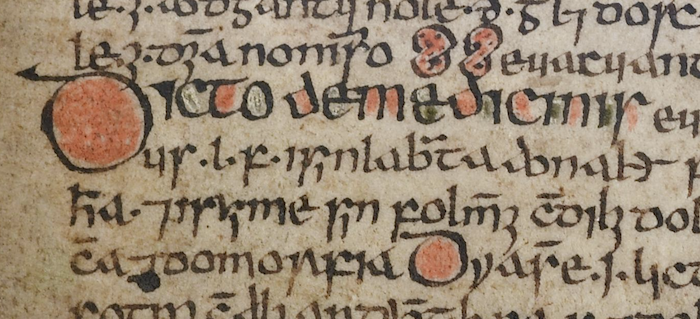

Meddygon Myddfai (The Physicians of Myddfai) is found in the Red Book of Hergest (Jesus College MS 111). It is a collection of herbal remedies and other medical advice attributed to a family of physicians from Myddfai, Wales. Written originally in Welsh, it combines Celtic medical traditions with those found in the wider medieval world. The Welsh and Irish both imported the larger part of their medical learning from the same Greco-Arabic tradition that served the rest of medieval Europe, referencing authors such as Galen, Discorides, and Avicenna. I selected this text for its content, length (At the beginning of the project I calculated ~185 pages when fully written down) and time period (the Red Book dates from the 1380s). I am transcribing from an 1861 translation which is free to read on Google Books.

The Script

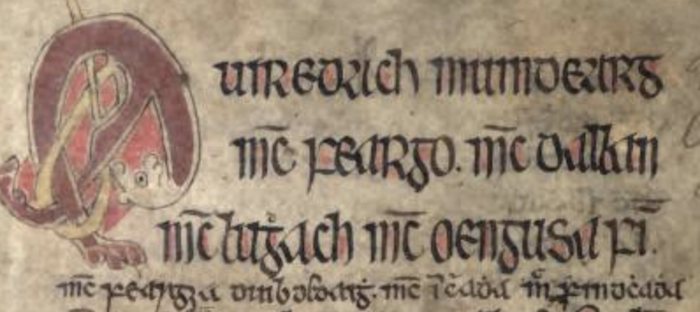

I accessed high-resolution images of Irish manuscripts at Irish Script on Screen. Zooming in on any of them is practically like holding the actual book up to your nose. I chose the Book of Ballymote as my primary exemplar and sometimes referenced other 14th-15th century MSS, such as the law text mentioned above.

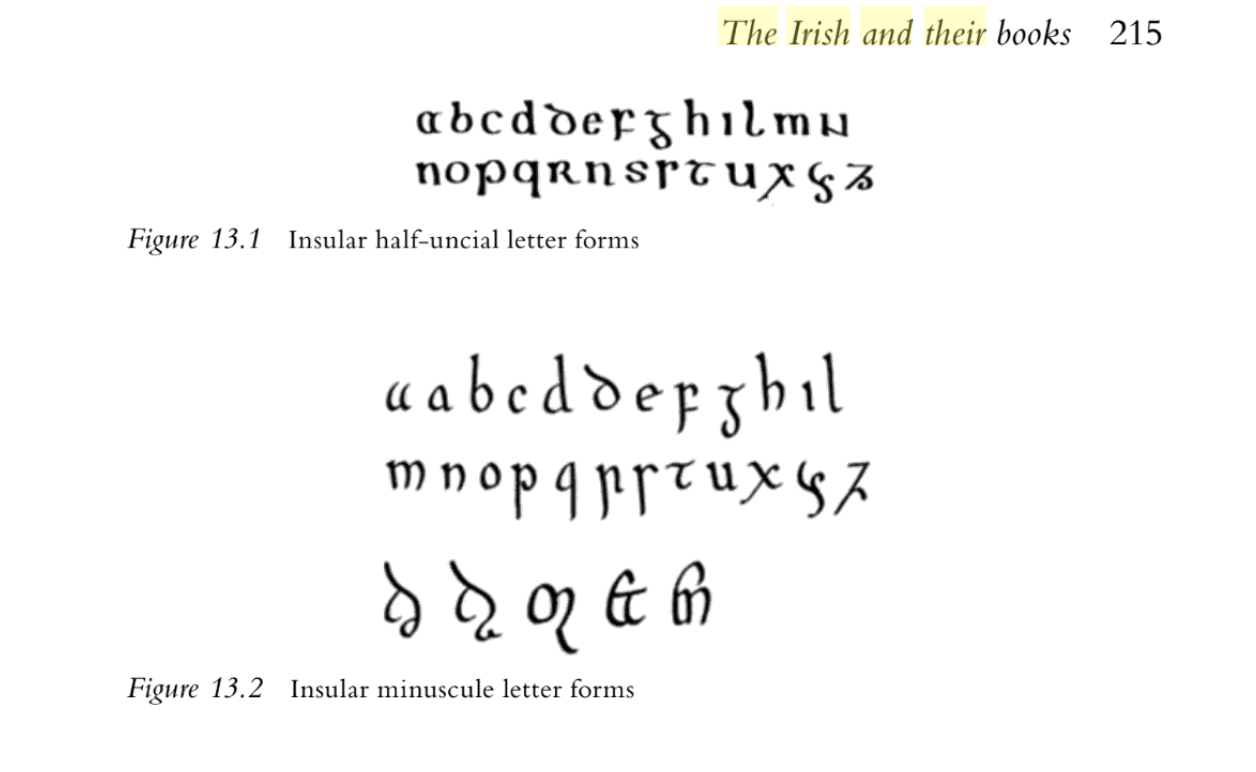

The hand in the Book of Ballymote, and the most common Irish book hand at the time, is an Insular minuscule. Professor Juan José Marcos' Manual of Latin Paleography breaks down the characteristics of this hand and helped me learn more about it. As to the particulars of the 14th century script, Tomás Ó Concheanainn says in 'The Scribe of the Leabhar Breac': "One of the most distinctive characteristics of the script of LB is the bold style of the serifs ... [earlier manuscripts] having none, or little, of the stiff angular thickening of the tops of letters, which so distinctly mark [the Leabhar Breac and Book of Ballymote]." This was a helpful starting place, but far more of my investigation into the script of BB was trial and error with my own pen.

The Irish in Early Medieval Europe: Identity, Culture and Religion. Ed. Roy Flechner & Sven Meeder. Google Books preview.

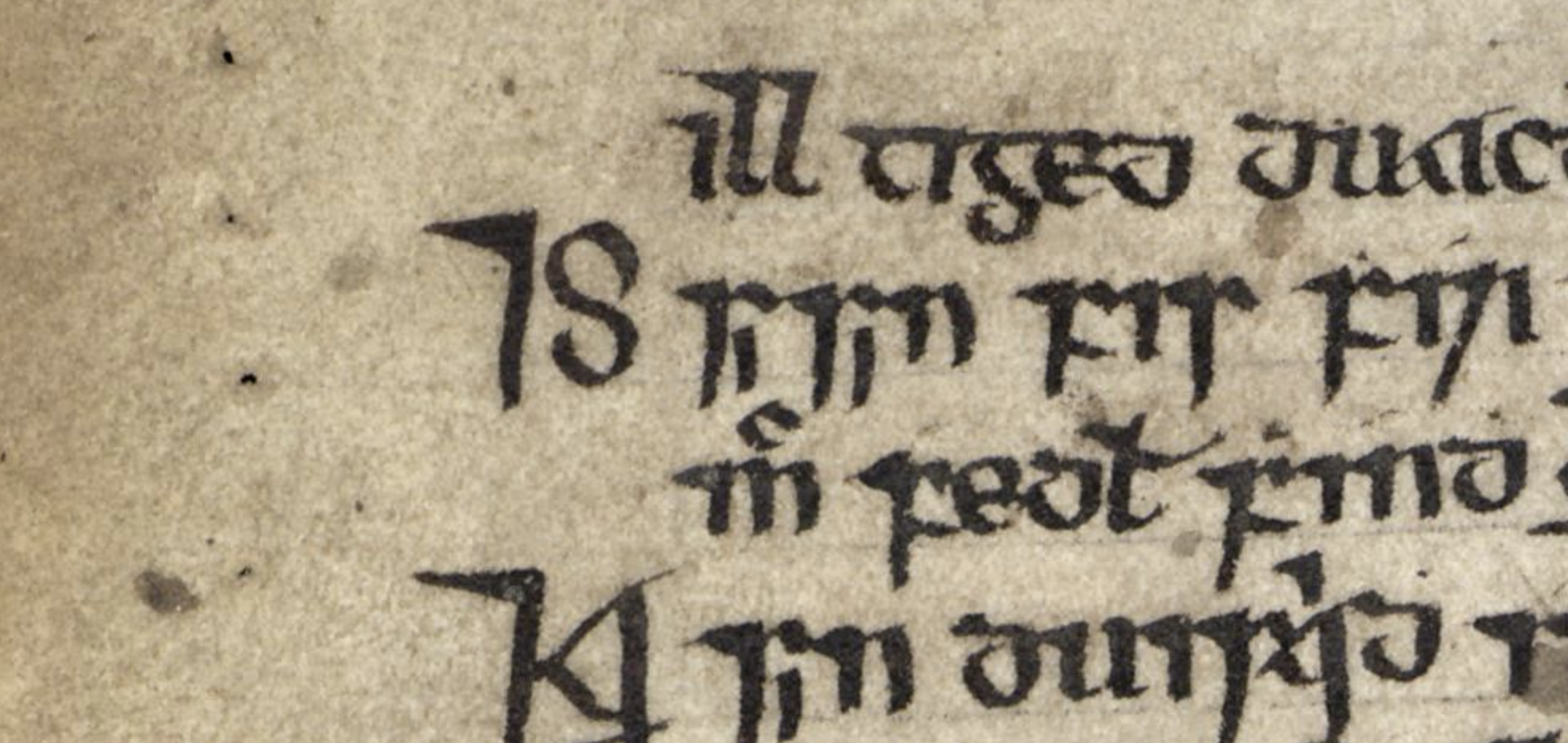

Medieval manuscripts often display multiple shapes for one letter. The Book of Ballymote has two different forms of ⟨r⟩, and tall and short versions of ⟨e⟩. Letter ⟨i⟩ is only dotted when it appears next to ⟨u⟩; this is because ⟨ii⟩ and ⟨u⟩ look very similar and might get confused. I had to decide how to represent ⟨w⟩, which does not appear in medieval Irish or Latin. I used the letter wynn, which appears in English versions of Insular script.

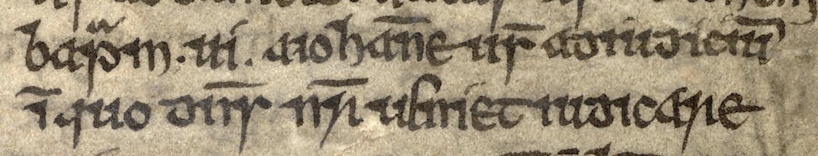

Medieval scribes used many abbeviations. They are usually marked with a line above, called a 'suspension stroke'. In order to decipher these and find more than appeared in BB, I referenced Tionscadal na Nod, or The Scribal Abbreviation Project, by the Collaborative Online Database and e-Resources for Celtic Studies (CODECS).

"[iohannem] baptistam .vi. a iohanne usque ad iudicium in quo dominus noster veniet iudicare..."

[John the] Baptist. 6. From John to the Judgement, at which Our Lord will come to judge...

Irish Script on Screen.

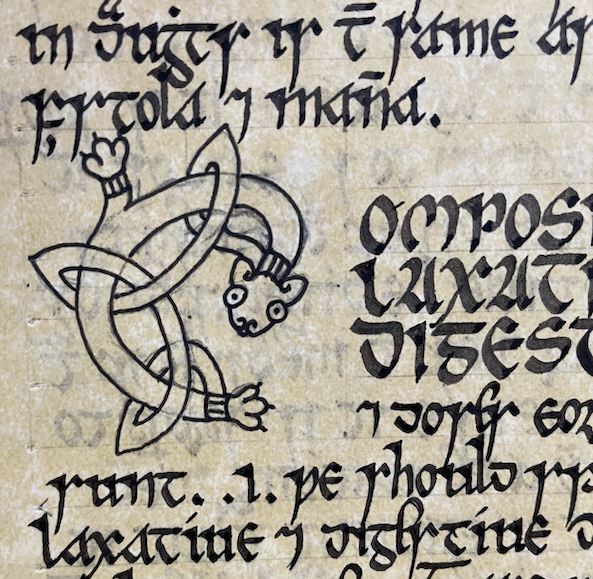

The Decoration

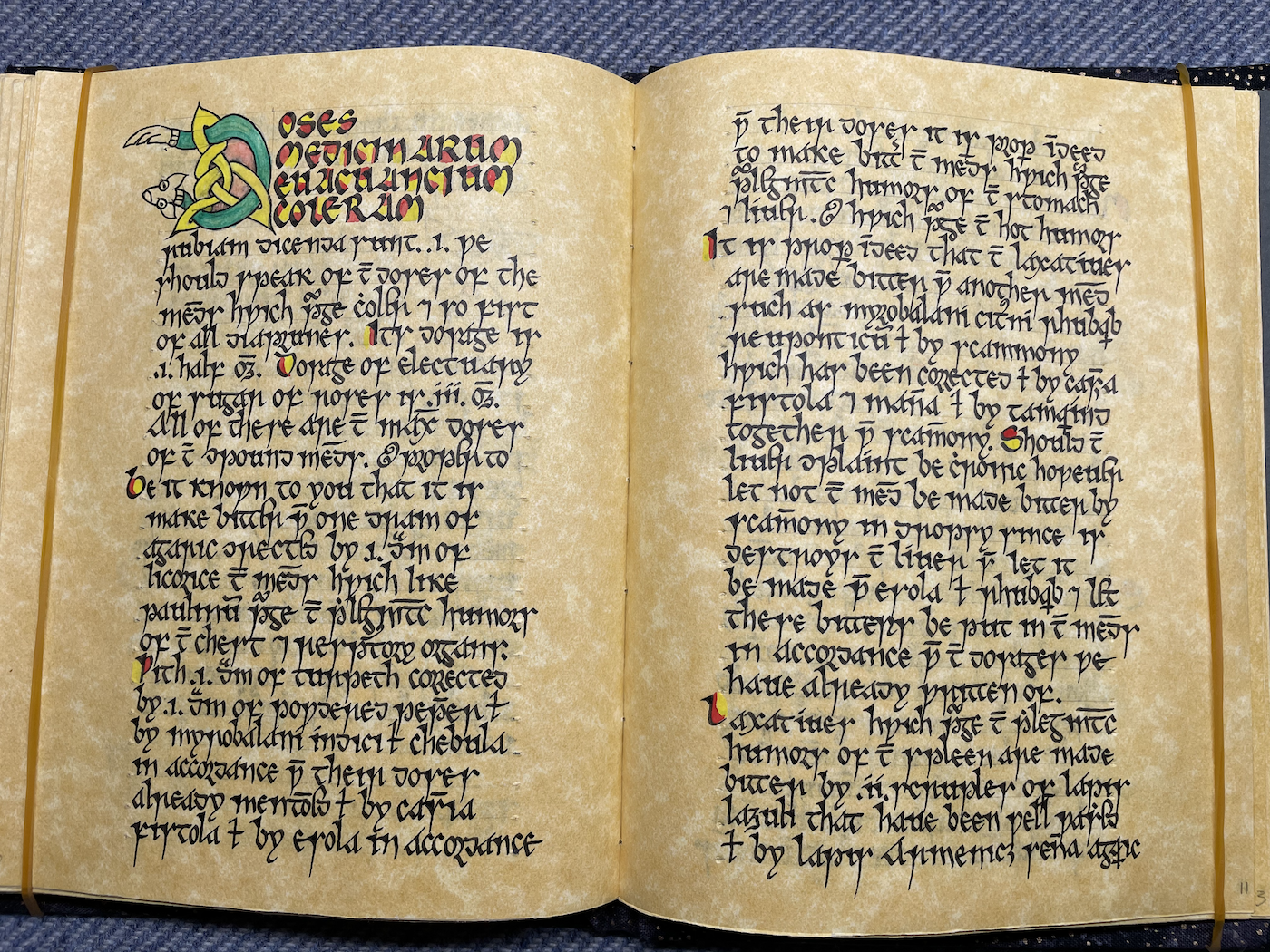

At the beginning of De Dosibus Medicinarum, the second text in CA, I decided to start adding decorated initials to the major section headings. These are based primarily on the Book of Ballymote. An extant copy of De Dosibus with decorated initials can be found in Royal Irish Academy MS 24 B 3.

Irish Script on Screen.

Irish Script on Screen.

Having spoken about the medicines [which purge]...

Decorated section heading from an Irish collection of medical treatises.

Royal Irish Academy MS 24 B 3, pg. 23. Irish Script on Screen.

The Page

Medieval methods for subdividing texts were different than those we used today. Conventions such as word spacing, punctuation, or paragraph divisions may or may not have existed in a given time or place. When you don't read the original language, it can be difficult to figure out what each punctuation or break signifies. Modern editors often punctuate and section transations for the reader's convenience, even adding headings that did not exist in the original. At the beginning of a section of BB, the capital overhangs the margin of the page. Sometimes, a capital is colored in with red and/or yellow pigment. I use this at the beginning of each remedy in CA. Each section ends with a ceann faoi eite, a piece of punctuation used for saving space. It marks the end of a section, and the continuation of the text from the line below, i.e. the next section, on the remainder of the line. It can be disorienting to try to read in this order at first, but I had to get used to it quickly. I leave myself wide margins, as are seen in many period manuscripts. Medieval scholars were fond of writing notes to themselves, either about the contents of the manuscript or about their personal lives. I put a marginal note in on Christmas eve, and on the first page I wrote after returning to America.

Irish Script on Screen.

The Size

While putting the manuscript together I began to get curious about the page count of similarly sized manuscripts. I have made note of manuscripts from several centuries in the British Isles which fit my informal idea of 'small books'. Manuscript historians usually make this count in folios, that is physical sheets rather than text pages. In modern page numbering we count the front and back of the same sheet as two 'pages' while a manuscript historian would count this as one folio.

| Book | Origin | Century | Content | Dimensions (mm) | Folios | ||||||

| Jesus College MS 22 | Wales | 15th | medical texts | 135x85 | 81 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Royal Irish Academy MS 24 B 3 | Ireland | 15th/16th | medical texts | 216x133 | 64 | ||||||

| St. Cuthbert's Gospel | Britain | 8th | Gospel book | 138x92 | 94 | ||||||

| Book of Dimma | Ireland | 8th | Gospel book | 175x142 | 74 | ||||||

| Codex Annamiticus | SCA | 21st | medical texts | 178x133 | 78 |

CA is about the middle of the pack among these manuscripts, which represent book production both before and after the goal date for CA.

Materials & Methods

Medieval scribes often ruled their pages by using a knifepoint or awl to make small pricks through multiple pages at a time. These could then be connected using a dry point (scoring the writing surface), lead, or ink. I prick through several pages at a time and rule between with a thin mechanical pencil. Rulings are visible on medieval manuscripts even today, so I do not plan to erase the lines.

Irish Script on Screen.

Medievan European books were written on parchment, that is, the skin from some large domestic animal that has undergone processing similar to rawhide or leather. Today, parchment is produced by few people, and is expensive. Rather than pay for actual parchment, I have opted for Speedball Calligraphy Parchment, which was given to me by a friend. It does not resemble actual parchment, but rather the popular idea of how aged books "should" look. Nevertheless, I was very grateful for the gift. In the future I would like to make a book from pergamenata, a modern writing surface which more closely resembles high-grade parchment.

Medieval ink recipes are often quite acidic; this was helpful to the scribes, because it allowed the ink to set in the not-very-absorbent parchment. This is not necessary with paper. Additionally, medieval inks can corrode modern metal pen nibs. (Someday I'll get good enough at cutting quills that I can use them for extended calligraphy.) For these reasons and for its ease of availability, I have opted for india ink, which can be gotten at most large craft stores. For the few red highlights I use gouache, a kind of watercolor paint which is the recommended medium for award scrolls in the SCA.

The dimensions of one page of Codex Annamiticus are as follows:

- Speedball Calligraphy Parchment is sold in 11x14 inch sheets. The bifolio is 11x7 inches, or one half of a Speedball sheet. The bifolio is folded in half to create two 5.5x7 folios.

- The top and bottom margins are 1/2 inch. The inner margin is 1 inch. The outer margin is 1.25 inches. The additional .25 inch will be cut off and sanded during the finishing of the text block.

- The line is .25 inch high. 24 lines fit between the margins.

Doing the work

Notes made during the creation of the Codex.

- I decided in the middle of the text to stop using ⟨v⟩ separately from ⟨w⟩. I don't remember why I wanted ⟨v⟩ in the first place; probably for English phonetic reasons? It was annoying me enough that I just switched to always using ⟨u⟩.

- As I went I realized I wanted abbeviations for English words that were common in the text, but not available in the lists of Latin or Irish abbreviations. For example the, with, fever, and together. I abbreviated these t, ƿ, fv, and tog, each with a suspension stroke.

- Tionscadal na Nod says that an abbreviation represents a certain string of letters "in the scribe's mind or in normalised spelling". Therefore, when using an abbreviation I sometimes deliberately misspell a word; for example, a ⟨p⟩ with a strikethrough on the descender should technically be read 'per', but I use it to write 'purpose'.

- Sections of the translation often begin For (illness). Rather than have an ⟨F⟩ start seemingly every other section, making for some unhelpful headings and a boring page, I started omitting this or otherwise revising the first line of each section so it begins with a more specific keyword.

- The text of The Physicians of Myddfai is so much shorter than my original estimates that I suspect an arithmetic error somewhere. Now that I've done quite a few pages CA, I can base a more accurate projection on CA pages completed versus MM pages read. I average about 145 words per page and 1.4 pages CA per page MM. At 33 pages CA I had completed 24 of 52 pages MM, or ~46%, giving a projection of only 71 pages CA to the entire text of MM. In order to reach a page count that deserves to be called a 'book', I have found an Irish version of Walter of Agilon's De Dosibus Medicinarum to add after MM is done. Walter of Agilon wrote around 1250, and his work was transcribed in Ireland into the 15th century. I'm very excited to be writing this text since my English version preserves the original Latin section headings, which make it easy for me to find them in the extant manuscripts and admire the decorated capitals.

- I decided to do an illuminated capital at the beginning of De Dosibus, based off the zoomorphic (animal-form) initials in the Book of Ballymote. At least one extant MS of De Dosibus does have decorated initials.

Progress on the work

Updates made during the process.

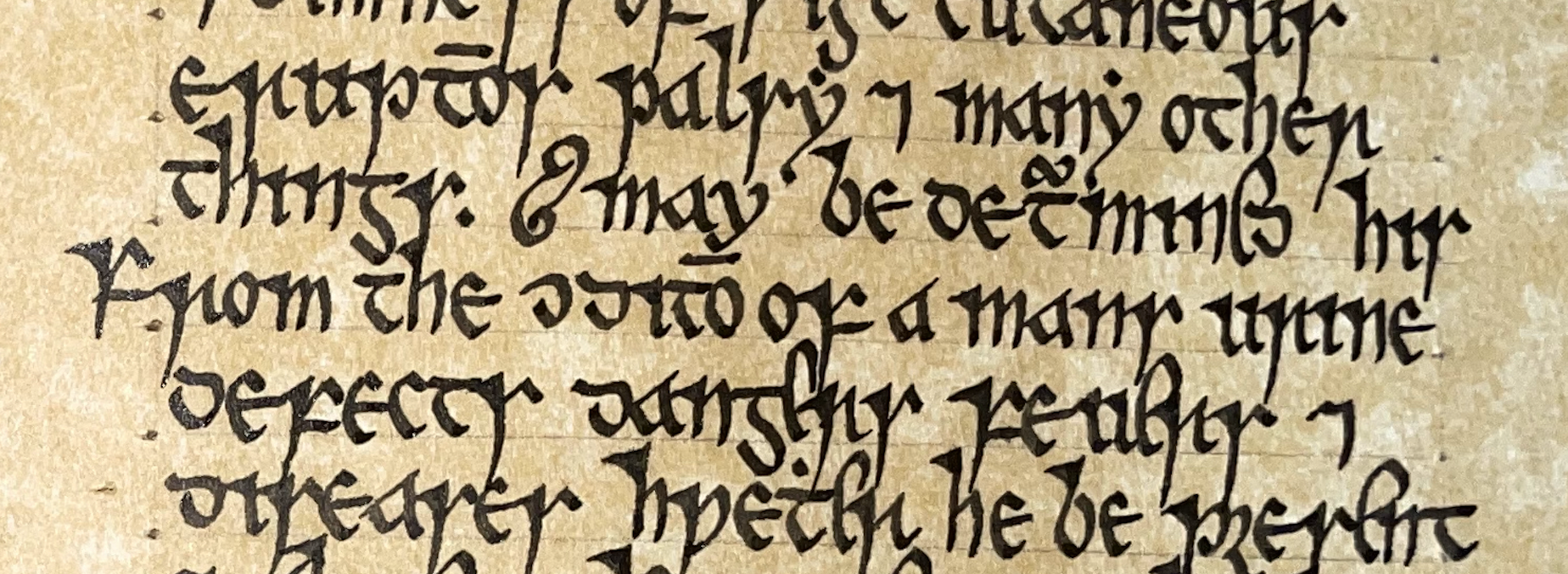

...eruptions palsy and many other things.

From the condition of a mans urine may be determined his defects dangers fevers and diseases whether he be present...

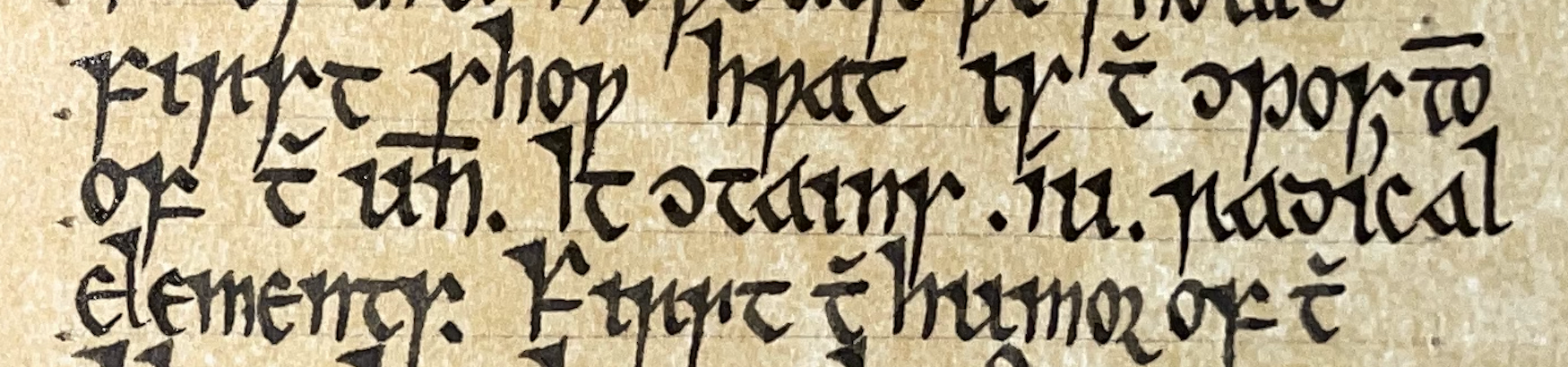

...first show what is the composition of the urine. It contains 4 radical elements. First the humor of the...

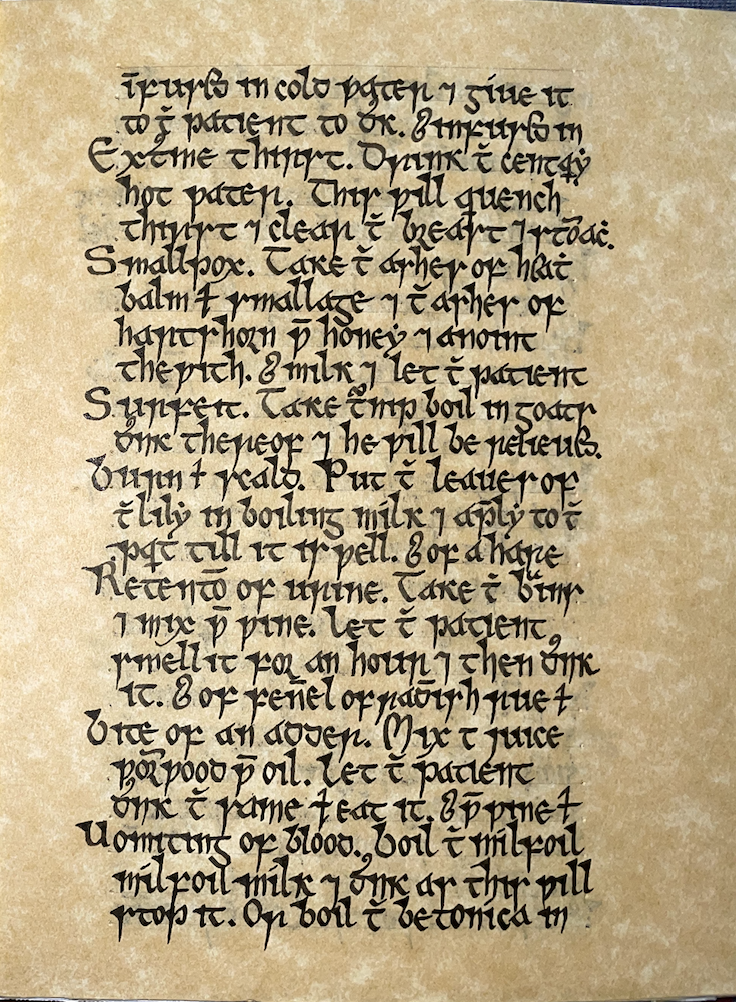

Extreme thirst...

Smallpox...

Surfeit...

Burn or scald...

Retention of urine...

Bite of an adder...

Vomiting of blood...

I learned on my return to America that ink, if not kept in the passenger compartment, freezes and thaws during a long flight. This causes the pigment to come out of solution. I was most likely using separated ink for my whole time in Vietnam. This was frustrating, to say the least.

Finishing the Book

I finished the book shortly after Pennsic War 49. While there, I met some brilliant crafters, many of whom had carried out projects that I had only begun dreaming of. I gained a lot of inspiration from them, and also learned that proper medieval bookbinding is far more complex and requires far more skills than I have. I could have let the finished pages sit while I developed those skills, but I decided against it. I am glad to say that my calligraphy visibly improves from the beginning of the book to the end, but unfortunately this also means the first half of the book is not up to my standard for "an artifact that can be worn and displayed as part of my SCA persona". Instead I gave the book a modern binding, using a cloth that could in no way be taken for medieval. The binding is not itself a work of creative anachronism, but just a means to hold together the scribal work. Overall I am very happy with what I have learned and achieved over the course of this work.

High-resolution images of selected passages can be found here. These are the first and last sections of De Dosibus.